Mark Gatiss (l.) with Arthur Burns, academic director of the GPP, and Oliver Walton, curator, Royal Archives, exploring the exhibition in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Picture: Royal Collection Trust © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2018

One of the most consequential subjects in the Georgian Papers is King George III’s madness, which historians and others have struggled ever since to understand and describe. We know from these archival materials that in 1788-89 he experienced a severe bout of mental illness. Cultural anxiety about mental illness, reticence about retrospective diagnoses, and privacy and other concerns about attaching such a diagnosis to a member of the royal family all meant that attention to this important subject was scattered. An assertion that the King’s illness was the result of porphyria (a theory now almost entirely discounted) plays an important part in Alan Bennett’s play and film. But based in part on materials now available through the Georgian Papers Programme, Sir Simon Wessely, Regius Professor of Psychiatry at King’s College London and the former President of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, notes that it is likely that the King suffered from ‘episodes of mania, a severe version of what we now label “bipolar disorder”.’ A recent analysis of some of the king’s writings, based on the methods of computational linguistics, suggests that even his use of language and phrasing can reveal the intensity of these manic phases.

From the materials in the Georgian Papers we can learn a great deal about eighteenth-century medicine, about how mental illness was handled at the time and subsequently in analyses of the king’s case, and about the effects of his illness on those around him. From doctors’ notes to the king’s own assessment, these items convey the immediacy of the challenges faced by his family, politicians and the court — and the medical practitioners charged with his treatment.

1. The King is moved to Kew

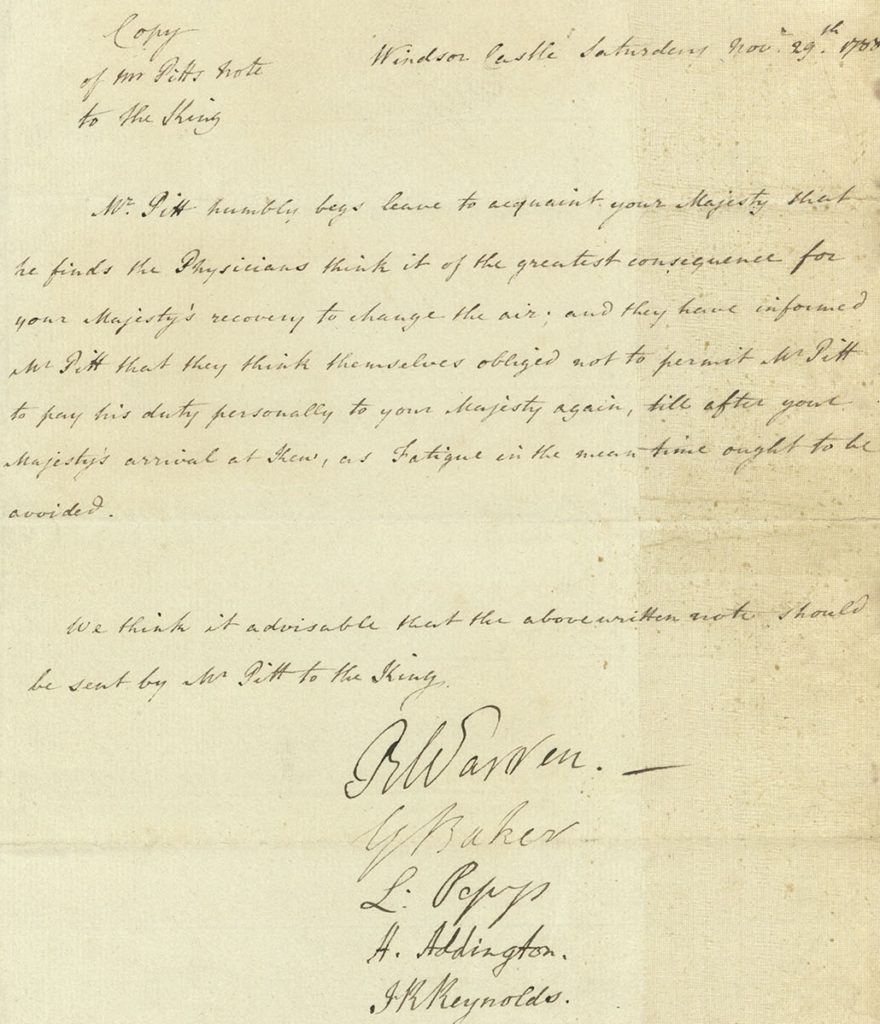

Letter from William Pitt to George III, 29 November 1788

Georgian Papers, GEO/ADD/2/3

Hard to read? Click here for a typed transcript, and here for the original catalogue entry; click on the image for a high-resolution image.

This draft text for a letter from William Pitt (1759-1806) to George III of 29 November 1788 marks a key moment in the treatment of the King’s malady, and a recognition of its seriousness.

Towards the end of October 1788 George III began to succumb to the attack of mental illness which forms the subject of The Madness of George III. Initially he was attended by Sir George Baker (1722-1809), baronet, president of the Royal College of Physicians, F.R.S., F.S.A., physician to the king; on 3rd November Baker called in the 78-year-old, but distinguished, physician William Heberden, who had retired to near Windsor. Then, as the King’s condition worsened during the night of 6th November, Baker urgently summoned Richard Warren (1731-97), F.R.S., physician to the King since 1763, and since 1787 to the Prince of Wales, and the following day Henry Revell Reynolds (1745-1811), the former physician to St Thomas’s Hospital. On 18 November, Sir Lucas Pepys, baronet (1742-1830), F.R.S., physician extraordinary to the King since 1777, was also called in; and on 24 November, at Prime Minister William Pitt’s suggestion, Anthony Addington (1713-90, father of the future prime minister Henry Addington, Lord Sidmouth, and his own family’s physician) joined the team, which by 29 November also included Thomas Gisborne (d. 1806), former physician of St George’s Hospital. It was this formidable phalanx of fellows of the Royal College of Physicians that set the date of 29 November 1788 for the removal of the King to the royal residence at Kew from Windsor Castle, on the grounds that there he could exercise unobserved and benefit from the air.

On the day, prime minister William Pitt the younger himself came up to Windsor in the morning, and was employed by the physicians in an unsuccessful attempt to persuade the King to cooperate after the latter had refused to leave his bed on being told of the plan. A second attempt entrusted to the equerries also failed.

The document before us was written at this point, the physicians instructing Pitt, in an ante room, to write the King the note set out in the document, reiterating the desirability of the removal to Kew, and insisting that no meeting between Pitt and the King should take place until it was complete. When shown it, the King became ‘much agitated’ and tried unsuccessfully to write a reply. Eventually the phalanx of physicians entered the room, at which point the King lunged at Warren, being restrained by his equerries. At about 3.45 p.m. the King finally departed for Kew once the equerries had promised to escort him.

The Madness of George III in part tells the story of how Francis Willis attained control of the King’s treatment despite lacking the elite medical credentials of the roster of physicians who signed this note. Elite as doctors, they were none the less of lower social status than their aristocratic clients, let alone the King — hence perhaps all signed to seek safety in numbers in recommending a course of action so unpalatable to the royal patient. This document is therefore also a reminder of how the illness itself had already served to invert customary hierarchies, as a team of doctors instructed the prime minister, in turn, to in effect command the King; the fact that the prime minister was still in his twenties may further have complicated the dynamics.

2. The equerry’s view: Robert Fulke Greville

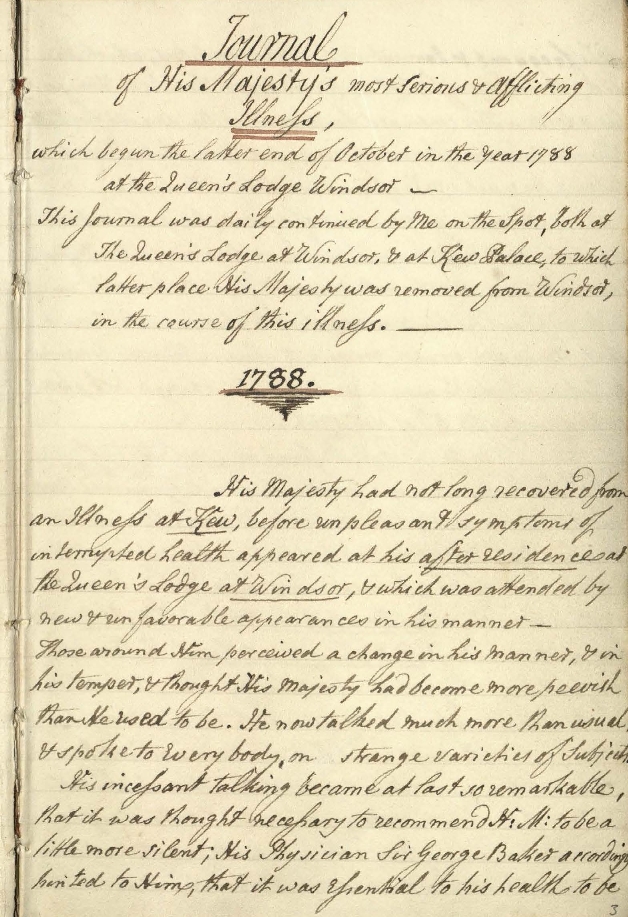

Robert Fulke Greville, Diary, Volume 2, Oct. 1788 – 4 Mar. 1789: ‘Journal of His Majesty’s most serious and afflicting illness which began in the latter end of October in the year 1788 at the Queen’s Lodge, Windsor’ .

Royal Library, Windsor Castle, RCIN 1047014

For high resolution image and to read more, click on document. Hard to read? For typed transcripts of the selected entries, click here. See the catalogue entry.

Robert Fulke Greville is a significant character in Alan Bennett’s play (the role created by Daniel Flynn on stage, and memorably incarnated in the film version by Rupert Graves), where he is simply referred to as ‘Greville’. As Bennett himself points out in his introduction to the play, he was not as constant a presence throughout the King’s illness in real life as he is in the play, while the final exchange in which his loyal service goes unrewarded while the duplicitous Fitzroy receives advancement is, like Fitzroy himself, a fictional invention.

Greville was initially a soldier, born in 1751 the third son of the earl of Warwick, serving in the 10th Dragoons and then the 1st Foot Guards, from which he retired in 1788 as a lieutenant-colonel. He also served as MP for Warwick between 1774 and 1780, returning to the House of Commons as MP for New Windsor between 1796 and 1806. In the 1796 election he was unopposed, for he had the backing of the Court interest. This reflected the fact that since 1781 he had served as equerry (meaning simply a military officer in personal attendance on the monarch) to George III. Although he left the post the following year, this was not the end of his connection with the royal court, for in 1800 he returned to serve as groom of the bedchamber, in which post he remained until dismissed in 1819 in a down-sizing of the Royal Household. Greville was evidently likeable — Fanny Burney nicknaming him ‘Colonel Wellbred’ — and was clearly valued by George III, on whose behalf he conducted correspondence concerned with the management of the royal parks. He died in 1824.

That Greville is known to history at all is largely related to the fact that he kept a diary, and that this is a key source for first-hand accounts of the detail of the King’s experiences during his illness of 1788-9. The diary makes clear Greville’s sympathy for the plight of George III and the humiliations, physical pain and distress visited upon the monarch both by his illness and the treatment prescribed for him. It also documents the reactions of others in the court to the crisis unfolding around them. For this exhibition, three significant entries were highlighted.

Early November 1788:

Greville opens this volume with a description of the very beginning of the King’s malady, heralded by a change in manner ‘His Majesty had become more peevish than he used to be’ and by incessant talking, agitation and incoherence.

5 December 1788:

The King’s health having worsened since late October, it was deemed necessary to call in Dr Francis Willis, who had had previous success with dealing with mentally ill patients.

20 December 1788:

The King’s condition becoming far worse ‘H.My became so ungovernable that recourse was had to the strait waistcoat: His legs were tied, & he was secured down across his Breast, & in this melancholy situation he was, when I came to make my morning Enquiries’

3. The therapeutic effects of Shakespeare?

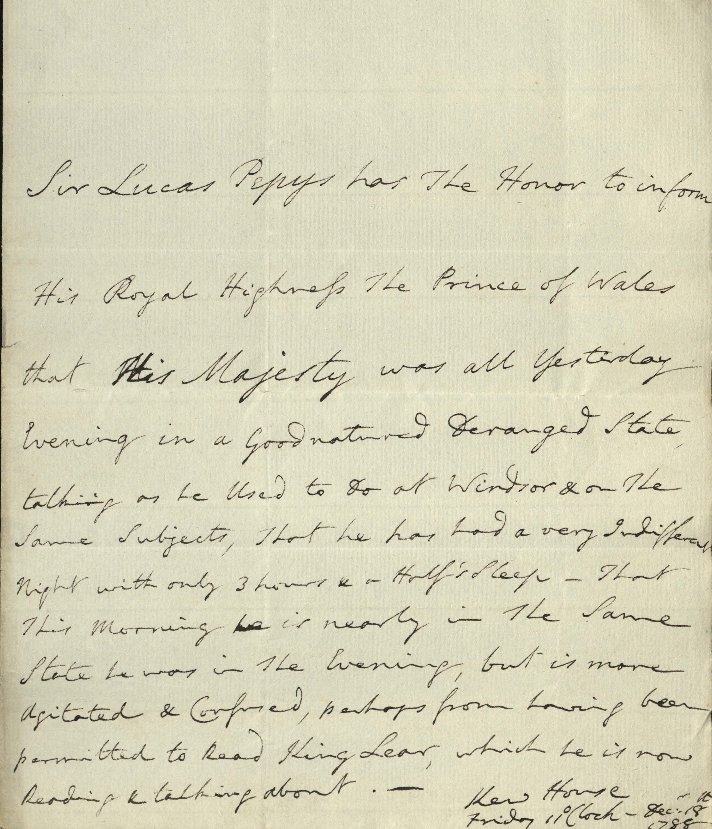

Letter from Sir Lucas Pepys reporting on a deterioration in George III’s health, 18 December 1788

Georgian Papers, MED/16/1/6

To see a high resolution image click on the document (and see fo. 13); for a transcription click here, or see the catalogue entry

In this letter Sir Lucas Pepys (baronet (1742-1830), F.R.S., physician extraordinary to the King since 1777, and one of the doctors who signed the first document in this exhibition), informs the Prince of Wales, on 18 December 1788, of a deterioration in George III’s health. The most striking feature of the letter is the cause to which he attributes this development: that the King had been reading William Shakespeare’s play, King Lear. Quite what this implies is hard to decide: it may simply be that the extreme emotions and tragic matter of the play were thought to have disturbed the King; but of course it is not impossible that the physician believed that the fact that Shakespeare’s tragedy explicitly dealt with a ‘mad’ King and the torments visited upon him may have agitated George through the parallels with his own plight. Our sense of the parallels between the two monarchs’ plight is heightened by the famous image of the King in his final illness engraved by Henry Meyer in 1817, with a flowing white beard, that recalls many depicitions of Lear on stage in our own time. It should be remembered, however, that the George afflicted in 1788-9 was only 50.

In The Madness of George III, Lear indeed features, but in a strikingly different way. In a memorable scene set at Windsor, George himself plays Lear in a reading of the play with Dr Francis Willis and Greville, insisting that Lord Chancellor Thurlow join in to play Cordelia. Bennett uses the obvious parallels between the King’s situation and that of Shakespeare’s monarch to touching effect, but here not to flag a decline, but rather as a significant marker of the King’s impending recovery in the return of some of his characteristic good humour and enthusiasm combined with his own realization that he has ‘remembered how to seem’ himself.

4. The King turns the corner

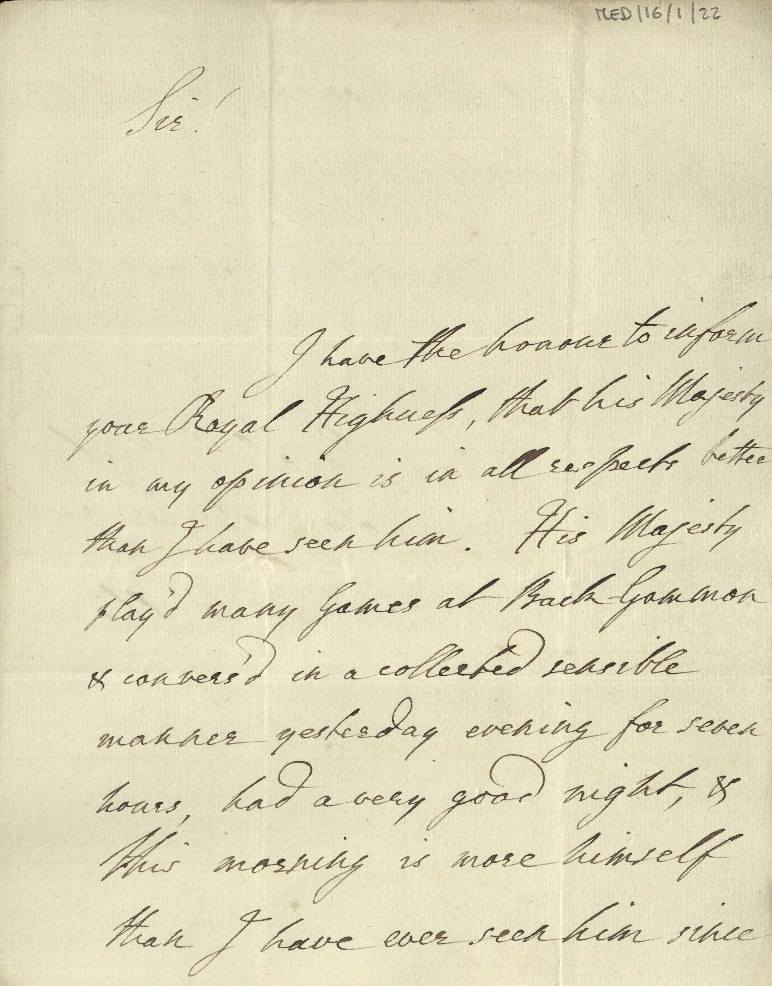

Letter from Francis Willis to the Prince of Wales, 1 January [1789]

Georgian Papers, MED/16/1/22

In this letter, dated 1 January 1788, but written on 1 January 1789, Francis Willis (1718-1807), the Lincolnshire doctor brought in to assist in the treatment of George III, writes to inform the Prince of Wales of a significant improvement in the King’s condition on the first day of the new year.

Willis is a pivotal character in Bennett’s play, as the key figure both in subjecting the King to a different regimen of treatment than the elite London physicians had previously prescribed, and as central to the King’s recovery. He had a quite different career path to the elite physicians — the son of a Lincoln cleric, he had attended Oxford University, where he had taken holy orders and held a fellowship at Brasenose College (of which he became vice-principal), before resigning as required when he married Mary Curtois in 1749. He then moved to Dunston in Lincolnshire, and turned his attention to medicine, graduating M.D. (once from Oxford) in 1759. He seems to have practised even before he received his degree, and was involved in the foundation of Lincoln General Hospital, of which he was appointed physician in 1769. Here he acquired a reputation for successful treatment of the mentally ill, and in 1776 he commenced a private sanatorium at his new residence of Greatford Hall near Bourne in Lincolnshire. Here patients worked in the fields around the house, and Willis attracted clients from a growing distance. One was the mother of Lady Harcourt, and it was her recommendation that led to the summons for the 70-year-old Willis to attend George III on 5 December 1788, shortly after the King’s removal to Kew.

To see the full document in high resolution, click on the image (and scroll to the third page). For a typed transcript click here, and to see the catalogue entry here.

Willis insisted on control over the King’s daily regime, and this, no doubt along with his inferior standing (not being a member of the Royal College of Physicians), led to tensions with the rest of the medical team, also reflecting his different therapeutic approach — it has been said that this was in effect the first call to a psychiatrist to attend such a distinguished patient. It is probably significant therefore that this bulletin is signed by Willis alone. A second bulletin —- this time signed by George Baker and Thomas Gisborne as well as Willis, was also dispatched to the Prince of Wales on 1 January. While this also noted an improvement, it spoke only of the King being ‘rather better than usual’ (Georgian Papers, MED16/1/21).

The King was showing signs of getting better, but it would be February before it became clear that the King was truely on the mend. Willis’s part in his recovery can be argued over, depending on whether one subscribes to McAlpine and Hunter’s thesis that he was suffering from porphyria (in which case his recovery from this physical disorder was largely coincidental) or to the now more widely accepted view that it was indeed mania (in which case it may indeed have been significant). Certainly Willis gained credit at the time: prime minister Pitt secured him a pension of £1,000 per annum from parliament, and his services were sought by others, including the Queen of Portugal: his new wealth enabled him to open a second asylum. When George fell ill once more, in 1811, it was again to a Willis that the case was allocated; only this time John Willis, Francis’s son, also a doctor, and who had also attended the King during the Regency Crisis (he was omitted from Bennett’s play no doubt as part of a wider strategy to avoid the piece being swamped by doctors!).

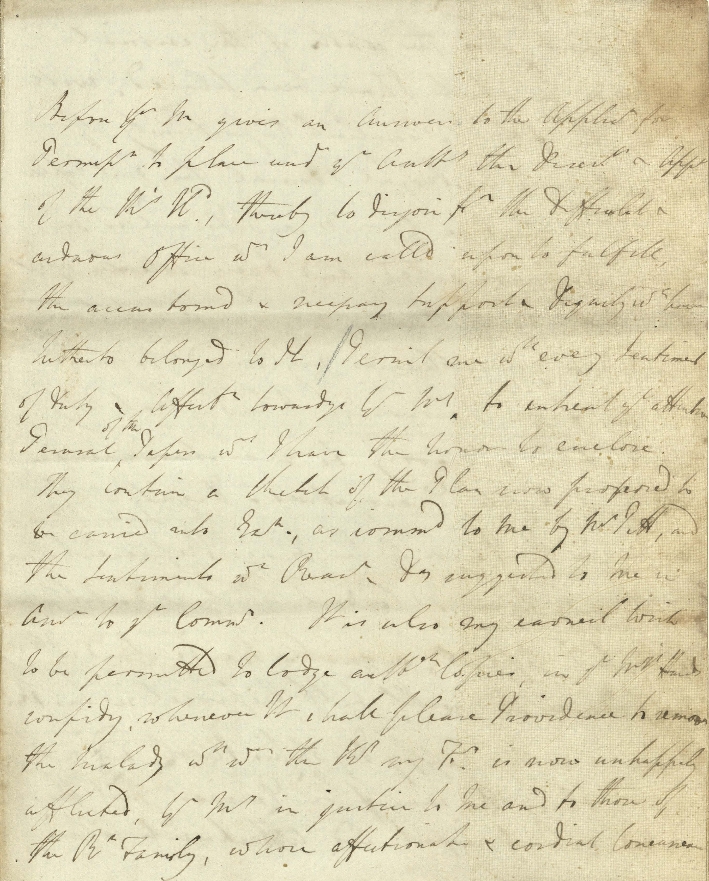

5. The Prince of Wales makes the case for his full authority as Regent

Letter by the Prince of Wales to Queen Charlotte regarding a plan for the proposed Regency. A copy is at GEO/MAIN/38429-33

Georgian papers, GEO/ADD/2/9

Alongside the narration of the course of the King’s illness, a second important theme running through The Madness of George III is the political ramifications that flowed from his incapacity in the context of the febrile political situation of the late 1780s, played out in part through the troubled relationship of George with his 26-year-old eldest son, then Prince of Wales, and the future Prince Regent/King George IV.

With the Jacobite rebellions still fresh in contemporary memory, and the monarchy still very much part of executive government, political opposition risked attracting accusations of treason or faction. One solution for those out of favour with crown or ministers was therefore to cluster around the figure of the heir to the throne, who often had his own personal reasons for welcoming challenges to the King or his government, quite apart from any political sympathy with the opposition on ideological or policy grounds.

Click on the document to read on in a high-resolution image of the letter, then here for the last page. It’s hard to read: you might find the typed transcription here easier! Click here for the catalogue entry

Just such a conjunction was in place when the King fell ill. The Prince of Wales was at the time closely associated with the ‘Foxite’ whigs, so-called after their most effective spokesman in the House of Commons, Charles James Fox. Fox’s political career had long placed him at odds with the monarch. This was partly over issues such as the handling of the American crisis, but also reflected Fox and his colleagues’ belief that the illegitimate use of royal power and corruption had kept them out of office despite their being both better qualified and more able than those who held office under the leadership of prime minister William Pitt. Pitt was presented as a tool of the crown and enemy of liberty, having come to power as a stipling of 24 in 1783 when the King had dismissed a coalition co-led by Fox which the King felt had been forced upon him.

On the Prince’s part, relations with his father had been severely damaged by the King’s disapproval of his son’s chaotic romantic life and financial profligacy, which had required in effect a humilating bail-out conditional on promises of future good behaviour; viewed from the Prince’s side, a situation brought about by unreasonable and unseemly parsimony on the monarch’s part. Were the King’s illness to force a regency as a solution to his incapacity, and a regency exercised by the Prince of Wales, both the opposition and Pitt’s supporters therefore recognised that it might lead to a dramatic change in their respective fortunes.

Genuinely distressed by his father’s illness and mother’s trials as the illness progressed, the Prince none the less had to engage with the potential consequences. A Regency Bill was of necessity prepared as the situation unfolded, but the terms on which the Regency should be enacted were inevitably the subject of contention between the interested parties, with Pitt and his allies seeking to limit the power to be exercised by the Regent, while the Foxites and Prince argued for an effective transfer of all significant royal power to the Prince. Throughout these discussions, particularly once there were signs of improvement, those involved had to weigh up not only the consequences of the arrangements proposed, but of the King’s reaction to such proposals once he recovered and resumed authority. The letter before us illustrates the Prince navigating this difficult path.

On 30 January 1789 the Prince of Wales wrote to his mother, Queen Charlotte, arguing against her accepting authority over the King’s Household during a Regency as proposed amongst the restrictions. The Prince protested that this would ‘disjoin from the difficult & arduous office which I am call’d upon to fill, the accustom’d & necessary support & dignity wh[ich] have hitherto belong’d to it’. Moreover, the Prince suggested, the King himself would share this view, since he was so concerned to protect the ‘just rights, prerogatives, & dignity of the Crown’. This long letter is a carefully constructed argument, which only just stops short of implying that the Queen might be subject to the influence of malign advisors. While historians have often highlighted the relationship between the Prince and his reformist coterie of friends centred on Charles James Fox as representing a factional attempt to capture the authority of the crown for the political opposition, here the Prince’s line of reasoning turns that argument on its head. He presents the declaration of a full regency to be the only way of preserving the full status of the crown. As we know from other documents, this sense that the crown was more important than any one holder of it, and that a prime responsibility of anyone who exercised its authority was to hand it on intact to a successor, was certainly one that George III shared, and the argument may have been couched with half an eye on a reading by a restored king in the future — as document 4 indicates, by the time this was written, there were signs that the illness might come to an end.

As a ploy, however, the letter was a failure. The Queen shared the message with Prime Minister Pitt, and in a reply drafted by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Thurlow, dismissed the Prince’s arguments. Within a few weeks, the King’s recovery would render the arrangements made in any case redundant.

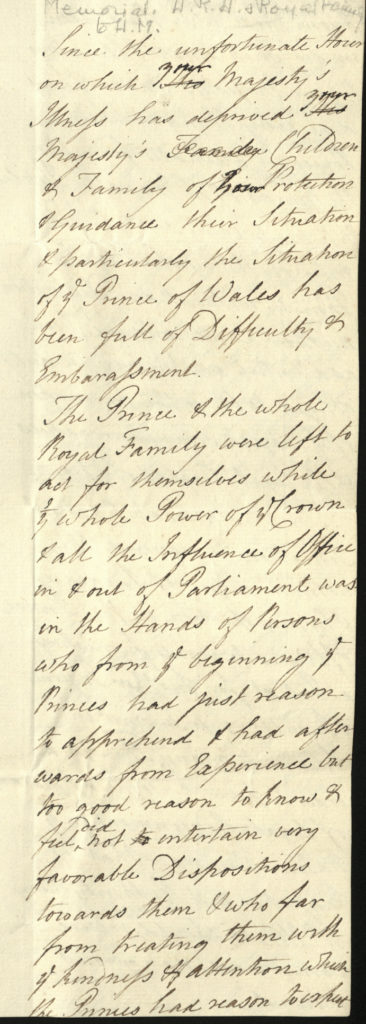

6. The Prince of Wales (‘and the Royal Family’) justify their conduct during the King’s illness

Memorandum from George, Prince of Wales, ‘and the Royal Family’, to George III, justifying their conduct during the King’s illness [1789]

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/38497-8

Click document to read on in a high-definition image. Click here for a typed transcript.

In this note we surely see an effort at damage limitation by the Prince of Wales as it became clear that the King was restored to health, and would be reviewing the events of his illness with interest. The Prince defends his own and his brother’s conduct against potential criticism that he anticipates from the King’s ministers, with Pitt now restored to a secure position threatened during the Regency Crisis by the Prince’s association with leading Whigs, above all Charles James Fox. As in the previous item, part of his argument is that his actions were motivated by an intention to preserve the integrity of royal authority, but here there is a much greater emphasis on the hostility the Prince had experienced from Pitt and his ministers. There may also have been a deliberate effort to imply that it was not just the Prince of Wales and Frederick that had been supposedly traduced by the ministers claimed to be briefing against them, but the whole Royal Family. It is noteworthy, moreover, that the Prince suggests that it was not only to the King that the brothers were to be misrepresented by their opponents, but to ‘Yr Majesty’s People’, indicating a recognition, that George III himself shared, that public opinion could not be ignored as a factor in politics, even by the monarch.

One theme emerging from our investigation of the Georgian papers is that a range of actors from generals to ambassadors and politicians, and indeed the King himself, knew the importance of their being other routes to presenting a case to the monarch than through the prime minister. Some of these backchannels are being revealed through the investigation of the papers of second-order individuals that have not hitherto been investigated by researchers, which contain material clearly intended for the eyes of the King. In this case, of course, it is hardly surprising that the Prince felt entitled to address the monarch and his father directly, but it was still clearly a priority for him to ensure that the recovered King was not only to hear Pitt’s side of the story of the Regency Crisis.

7. Now it is over ….

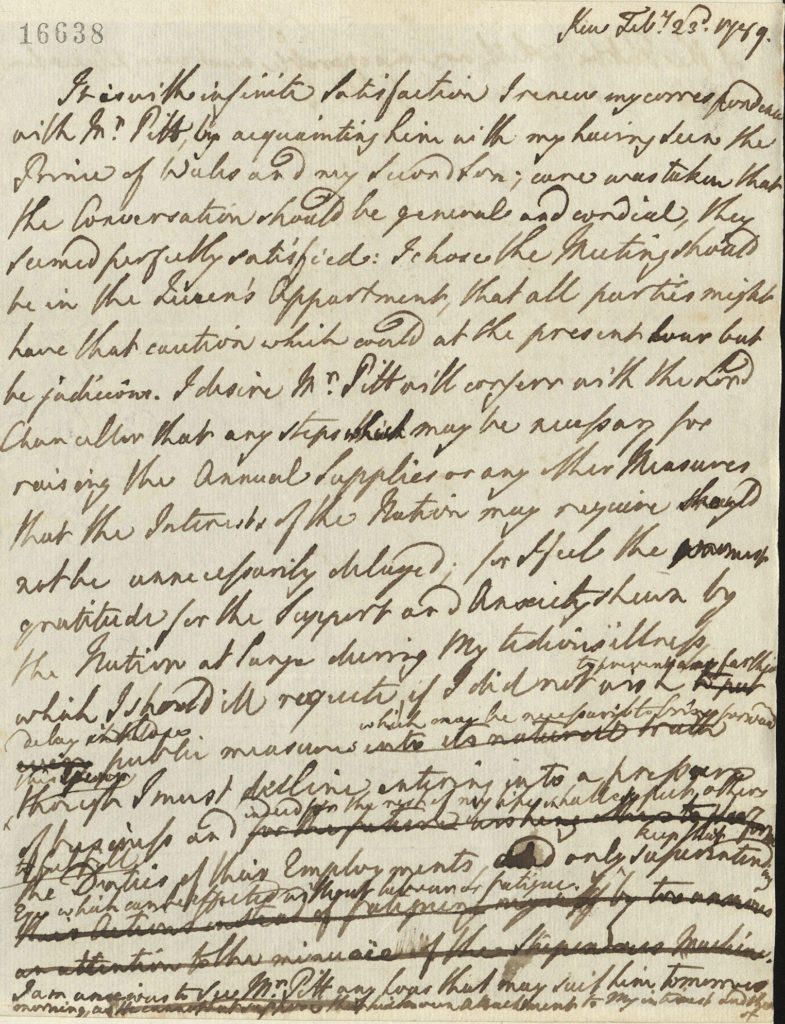

A memorandum by George III regarding the renewal of correspondence with Prime Minister William Pitt, 23 February 1789

Georgian Papers, GEO/MAIN/16638

To read in full in a high-resolution image, click the document. For a typed transcript, click here.

On the 23rd of February 1789, in the letter of which this is a draft, George III resumed his correspondence with his prime minister. He both looked back over the ordeal of his illness and also looked forward to the resumption of business as usual. Within its short compass it captures a number of key dimensions of both the episode of the King’s madness and of his character. The number of crossings out is a familiar feature of many of the King’s writings composed at times of strain, apparently indicating his concern to find the right words when he felt deeply. In its contents it speaks to his courage and resilience, on which many contemporaries commented; his capacity for self-awareness when not overcome by temper or emotion; his sense that the national interest was ultimately of more significance than his own welfare; the way in which the crisis cemented a relationship with Pitt that would endure until their differences over Catholic Emancipation would drive them apart in the new century; and the additional circumspection with which the King would now approach his relationship with his eldest boys. In thus looking back on his illness, but also opening up aspects of his wider character, it serves as a perfect bridge to the second part of the Exhibition, where we explore the character and interests of the King and his family, above all his relationship with Queen Charlotte, such a powerful presence in the play.